Old German Tablature Notation

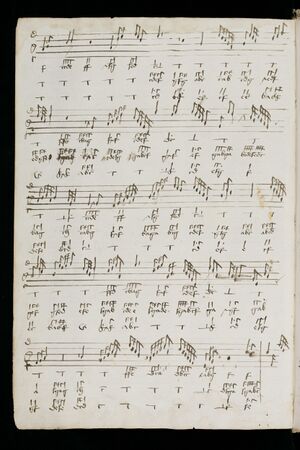

The term "Old German Tablature" refers to a style of notation popular among German-speaking organists in the 15th and 16th century. Unlike the "new" notation, it was only rarely used to write down compositions not to be played on a keyboard instrument. Surviving examples show that it could readily support pieces between two and ten voices.

Overview

The defining feature of old German tablature is the usage of black mensural notation for the voice that is highest in pitch (the superius, as it is often referred to). The organist is usually expected to play this voice in their right hand, using their other hand and both feet to play the lower voices, which are invariably given in letters. The specific style of notation varies significantly between manuscripts, but a few common elements can be observed:

- In the superius, all stems point upwards, and a downward stem is used to denote chromatic inflections (if it appears plain or crossed with a short, diagonal stroke) or ornamentation (with a loop or curve at its end). Some scribes allow for downward stems that are both crossed and looped, some prefer to only denote the ornament in such cases. A triangular flag may denote triplet rhythm or a change in mensuration. In the last third of the 15th century, a curious form of shorthand emerged - in a passage of many notes moving in uniform values, only the first is given with the appropriate amount of flags, while the rest are notated as noteheads only. A double-sided repetition symbol, the shape of which varies between sources but always remains recognisable, can be placed above the staff, wherever it is most appropriate - the specific manner in which the repetition is carried out depends on the musical context.

- In the lower voices, the symbols used generally agree with what is now known as Helmholtz pitch notation: the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, H belong to the white keys, while for the black keys a specific set of Cis, Es, Fis, Gis, B is used. These are used even in contexts where the enharmonic spelling should be preferable (presumably for the sake of convenience), with minimal exceptions. At first, the symbols of the black keys may prove difficult to recognise: the raised tones are only written with the base letter and a long S next to it, the I being omitted, and Es, despite being written without any shorthand, tends to become distorted by the scribe's handwriting. In terms of octave displacement, a lowercase letter belongs to the octave directly below Middle C, and an uppercase letter (only in 16th century sources) to the octave below that; for octaves above Middle C, horizontal lines should be progressively added above the lowercase letter. Note that, as the higher ranges were usually occupied by the superius, it is rare for the letters to intrude into the double-dashed octave - the specific implementation tends to vary between sources, with some lacking the provisions for such notation entirely. The rhythm is denoted with dots and vertical lines above the letters. Given that the shapes of the notes must agree between the superius and the letters below, a note with a dot above its letter has the note value of a semibrevis (in richly ornamented works of the Paulomimes, semisemifusae are a common sight).

- Where measure lines were not written, the scribe denoted the limits of a measure with minute horizontal gaps between groups of letters. A "=" symbol, sometimes vertical, is often used when a measure is cut off prematurely at a page's right margin, to let the reader know that its continuation will follow. Notes can be, and ocassionally are, written across barlines.

Scribal errors happen often, as do intentional omissions of commonly understood interpretative details, and they are of different nature when occuring in the superius and when occuring in the lower voices. It is common for the entirety of the superius to be written without any accidentals or for some of its notes to have an incorrect rhythmic value assigned (whether by an inappropriate usage of stems, or flags). Somewhat less frequently, accidentals were left out in the lower voices as well. Sections of the top voice are also prone to being written a line too high or too low, producing unmusical results. Just like with normal mensural notation, there are many cases where the total length of a measure in the superius does not match itself as given by the letters.

Specific manuscripts

More details and links will be added soon.

Ileborgh tablature

The letter notation in this source is unique: to save space, two-voice accompaniment is written horizontally, so that a pair of letters always takes up the space below a single "measure" in the superius. It is commonly accepted that this signifies the usage of double pedal, the left letter being intended for the left foot and likewise on the right side. Further comment on this manuscript is precluded by lack of access to its facsimile or published research of acceptable quality.

Lochamer-Liederbuch

The second half of the manuscript (that is, the part which contains pieces in organ tablature) can be further divided into two sections according to the manner in which the notation was written. The point at which a new octave begins was chosen to be between B and H, for practical reasons. Except for staves written later into the bottom margin in order to keep a piece within the boundaries of a single page, every staff has seven lines. For the clef, the letters C, G, and D are used, with abstract symbols for F and D (a flower).

- The first section is written in a clear and legible hand. It gives an overall impression of a standardised, consistent system of notation, with only minimal deviations from the norm. Barlines are present and most measures have a regular length of three semibreves (this suggests that tempus perfectum is assumed); only a few measures are longer than that, typically two or three times the normal amount. In the superius, chromatic inflections use a crossed downward stem. A looping downward stem, identical both in shape and usage to that present in the Buxheim manuscript, is used in the last two pieces ("Benedicite Almechtiger got" and "Domit ein gut Jare"). Outside of that, it appears that the only notation for an ornament is a double-stemmed notehead with flags on both stems. It typically occurs in passages of uniformly-moving minims, only twice (towards the end of the "Fundamentum breve cum ascensu et descensu") does it appear in contexts where the Buxheim loop may be considered appropriate. However, Apel claims that it is identical to a semiminim, specifically one on the weak beat, always adding a dot to the preceding minim when transcribing.

- Out of the lower voices, the tenor is written in large black letters, with a double letter being used for its last note (invariably a longa). Note that the symbol for a final D somewhat resembles that which later notation uses for a common Es, and, similarly, a double G may sometimes look similar to a Gis. At the beginning of a piece or section thereof, a capital, sometimes double, letter is used. Very rarely, multiple letters occur in other places as well; the meaning of such usage is obscure. In some such cases, it may refer to repetition of a note, or perhaps to signify that an unusually long note is to be played. No notation is used for notes of the double-dashed octave, as the lower voices never move higher than g'. The contratenor may be written in either red or black ink, its letters appearing both above and below those of the tenor. Note values are written in red ink above the letters, but only in cases where there are more than three notes in one measure.

- The latter part is distinct by the absence of decorative red ink (except for two pages) and prevalence of white mensural notation for the superius; it begins with black notation, but eventually moves to white midway through a piece (the "Paumgartner"), suggesting that the scribe first wrote empty noteheads and intended to fill them in later. A greatly expanded selection of keys is now available for the lower voices: the notes Es, Fis, Gis, and even Dis (in an incorrect context, no less) appear in this section for the first time. While still clearly legible, the handwriting is not as orderly as before. In the second-to-last "Praeambulum super F", there are two voices notated with mensural notation in the upper staff. The tablature on the last page returns to the notational practice observed throughout the first section.

A "pausa" ("pau", abbreviated) appears a few times among the letters.

The Buxheim organ book

Throughout the manuscript, seven lines are used for staves, exceptions being the six staves of five lines following the last piece of the collection, as well as the extensive "Tabula" on the last folio, which uses twelve lines and serves to explain the letter notation. Rests are now represented with proper symbols indicating their exact lengths. Changes in mensuration occur more frequently than in other manuscripts, accompanied by common time signature symbols or inscriptions describing the change taking place. The tempus can be determined from the size of a measure, and a specific subdivision is even mentioned in the titles of certain pieces (such as "trium" or"quattuor notarum") - this ties into the contemporary theory of dance arrangements, where, for example, a basse danse (a type commonly occuring in the Buxheim organ book) would require six notes to occur for every note of the adapted tenor. In cases where a brevis needs to be chromatically altered, the downward stem always receives the diagonal dash, to prevent confusion with a longa.

- Out of the nine fascicles that constitute the manuscript, almost all music in the first eight was written by a single scribe, with five pieces added at the end in another hand. The handwriting observed throughout this corpus is orderly and legible, with all notes of a measure evenly spaced across its width. Barlines are present; as in the Lochamer source, a measure may sometimes take on a whole-number multiple of the regular length. White mensural notation appears in two pieces here.

Tabulaturen etlicher Lobgesang und Lidlein

As the only surviving example of printed old tablature - and possibly the earliest instance of printed organ music - the notation of Schlick's Tabulaturen differs notably from the other sources. The staff has six lines. Some of the notes that are placed on or below the top line are flipped in such a way that their stem points down. Chromatic alteration is indicated by a small loop connected to the notehead, opposite the stem. There are no symbols for ornaments of any kind. The mensuration ocassionally changes in the middle of a piece, marked by an appropriate symbol; sections in perfect time use looped, almost triangular flags on their semiminims and fusae. Like in the Buxheim organ book, lowercase letters are used for notes of the great octave; however, Schlick eliminates ambiguity by adding a horizontal line below the letter. A new octave begins with C.

Fundamentum of Hans Buchner

Hans Kotter tablature

Fridolin Sicher tablature

Leonhard Kleber tablature

Tablature of Jan of Lublin

Cracow tablature

References

Facsimiles of the aforementioned manuscripts can be accessed from their respective pages.

Kite-Powell, J. (2022) German Keyboard Tablature. https://www.academia.edu/53290890/German_Keyboard_Tablature

Southern, E. (1963) The Buxheim Organ Book. Brooklyn, Institute of Mediaeval Music.

Apel, W. (1938) Early German keyboard music. The Musical Quarterly, vol. 23.