New German Tablature Notation

"New German Tablature" (de: die Buchstabentabulatur or Neue deutsche Orgeltabulatur) is a notation style used by north-German organists from around the late 16th-mid 18th centuries.

New German Tablature Notation is basically identical to the letter notation of Old German Tablature Notation.

This article is a stub, you can help expand it with more information and citations!

Notation

Music written in New German Tablature Notation is written in an "open-score" format in which the voices is written above and below each other with no concept of combining voices on separate staves. Virtually all manuscripts in New German Tablature Notation write each system across both pages, unlike modern staff notation where each system goes across one page only.

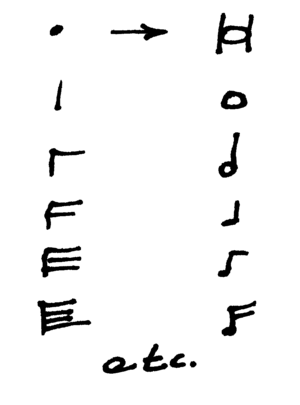

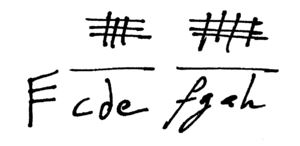

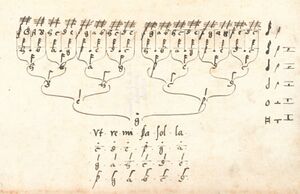

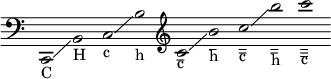

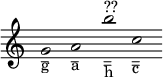

The letters are written in what is now called Helmholtz Pitch Notation using B and H for (in english) B-Flat and B-Natural. The bass octave is written in capital letters, the tenor in lowercase, and subsequent octaves written with different number of horizontal lines above the letter.

Some manuscripts wrote notes in the soprano range (c''-h'') with one wavy or dotted line instead of two solid lines.

The note at which the octave changes does vary. In almost all manuscripts, the octave starts at C. However, the octave sometimes starts at H (notably, Bach's copy of the Prelude in E Minor by Nicolaus Bruhns does this). This cutoff point is almost never explicitly stated and must be determined by examining the music itself.

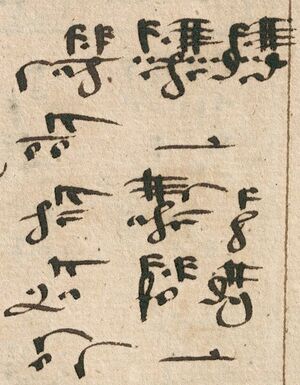

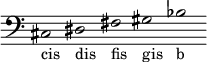

For accidentals, the sharp is virtually always used instead of the flat equivalent (even when it is enharmonically incorrect) except for B-Flat which is written B. Note that tablature notation has no notion of accidentals carrying through to the end of the measure, like staff notation; each note is written just as a sharp or natural.

A down-right stroke (representing -is) is appended to the letter.

An overview of the letters and how they appear in various manuscripts appears below.

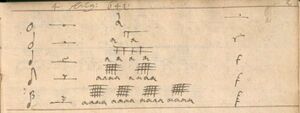

Rhythms are written in the following way: a dot for a breve, a vertical line for a whole note, and then adding one horizontal flag to the top of the vertical line for shorter note values.

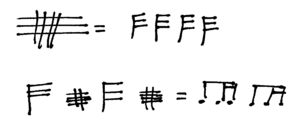

Notes of the same rhythmic value are frequently beamed together (similar to modern notation). When this happens, a grid of horizontal and vertical lines is drawn, in which the number of vertical lines shows the number of notes and the number of horizontal lines shows the rhythmic value.

For a rest, the rhythmic symbol is written in place of the note name. The same rhythmic sign is used, except for whole-note rests, which are drawn by a symbol that looks like a half rest in modern notation, and a breve rest by a symbol looking like a whole rest.

Handwriting Table

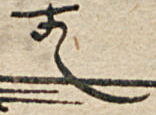

| C | CIS | D | DIS | E | F | FIS | G | GIS | A | B | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-B Ms. Lynar B 3 |  |

|

|

|

| |||||||

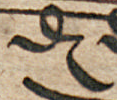

| c | cis | d | dis | e | f | fis | g | gis | a | b | h | |

| D-B Ms. Lynar B 3 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

Notes

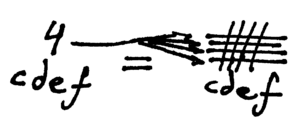

Sometimes, the scribe uses a shorthand to show rhythmic values, writing a number instead of the cross of horizontal and vertical lines. In this case, the number means the number of horizontal lines (meaning the rhythmic value), and the number of notes must be determined by surrounding context.

In D-LEm Becker II.6.19, the octave cutoff is h, but bass H is written as H instead of h (that letter does not exist in this writing).

References

Willi Apel. The Notation of Polyphonic Music. Fifth Edition. Cambridge, MA: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1953. Reprinted 1961. 21-37.

Jeffery T. Kite-Powell. The Visby (Petri) Organ Tablature: Investigation and Critical Edition. Volume 1. Wilhelmshaven: Heinrichshofen. p.37-41.