Old German Tablature Notation: Difference between revisions

→The Buxheim organ book: finished section content-wise |

new general descriptions for each time period category; moved one source across categories to better represent its contents; new reference |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

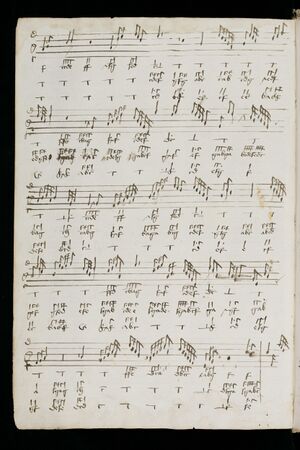

[[File:Sicher tab page.jpg|thumb|right|A page from the [[Fridolin Sicher Tablature]] showing an example of Old German Tablature Notation]] | [[File:Sicher tab page.jpg|thumb|right|A page from the [[Fridolin Sicher Tablature]] showing an example of Old German Tablature Notation]] | ||

The term "'''Old German Tablature'''" refers to a style of notation popular among German-speaking organists in the 15th and 16th century. Unlike the [[New German Tablature Notation|"new" notation]], it was only rarely used to write down compositions not to be played on a keyboard instrument. Surviving examples show that it could readily support pieces between two and | The term "'''Old German Tablature'''" refers to a style of notation popular among German-speaking organists in the 15th and 16th century. Unlike the [[New German Tablature Notation|"new" notation]], it was only rarely used to write down compositions not to be played on a keyboard instrument. Surviving examples show that it could readily support pieces between two and six voices. Examples of more developed notational styles seem to have originated in southern and south-western Germany in two main groups centered around particularly respected organists ([[Conrad Paumann]] and [[Paul Hofhaimer]] respectively). | ||

== General overview == | |||

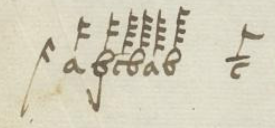

[[File:B_ornament.png|thumb|An example of the ornament sign being used on a letter (from Kleber's tablature).]] | |||

The defining feature of old German tablature is the usage of black mensural notation for the voice that is highest in pitch (the ''superius'', as it is often referred to). The organist is usually expected to play this voice in their right hand, using their other hand and both feet to play the lower voices, which are invariably given in letters. The specific style of notation varies significantly between manuscripts, but a few common elements can be observed: | The defining feature of old German tablature is the usage of black mensural notation for the voice that is highest in pitch (the ''superius'', as it is often referred to). The organist is usually expected to play this voice in their right hand, using their other hand and both feet to play the lower voices, which are invariably given in letters. The specific style of notation varies significantly between manuscripts, but a few common elements can be observed: | ||

=== Superius === | |||

In the superius, all stems point upwards, and a downward stem is used to denote chromatic inflections (if it appears plain or crossed with a short, diagonal stroke) or ornamentation (with a loop or curve at its end). Some scribes allow for downward stems that are both crossed and looped, some prefer to only denote the ornament in such cases. A triangular flag may denote proportions or a change in mensuration, typically to signify temporary ternary division of note values when binary division is used throughout the rest of the piece (the Buxheim manuscript, which uses generally larger note values than later sources, utilises the standard technique of ''color'' in cases where such a change occurs among note values too large to be written with flags). In the last third of the 15th century, a curious form of shorthand emerged - in a passage of many notes moving in uniform values, only the first is given with the appropriate amount of flags, while the rest are notated as noteheads only. A double-sided repetition symbol, the shape of which varies between sources but always remains recognisable, can be placed above the staff, wherever it is most appropriate - the specific manner in which the repetition is to be carried out depends on the musical context. The ''custos'' appears often, though not everywhere. | |||

=== Lower voices === | |||

''Note: Even though the letter notation may look similar to [[New German Tablature Notation#Notation|its counterpart in the "New" tablature notation]], there are some differences between the two.'' | |||

In the lower voices, the symbols used generally agree with what is now known as Helmholtz pitch notation: the letters ''C'', ''D'', ''E'', ''F'', ''G'', ''A'', ''H'' belong to the white keys, while for the black keys a specific set of ''Cis'', ''Es'' (or ''Dis''), ''Fis'', ''Gis'', ''B'' is used. These are used even in contexts where the enharmonic spelling should be preferable, with minimal exceptions (presumably for the sake of convenience). At first, the symbols of the black keys may prove difficult to recognise: the raised tones are only written with the base letter and a long S next to it, the I being omitted, and ''Es'', despite being written without any shorthand, tends to become distorted by the scribes' handwriting - in later sources (and most manuscripts written in the newer style), the symbol is formed differently and represents a ''Dis'' note instead. | |||

Scribal errors happen often, as do intentional omissions of commonly understood interpretative details, and they are of different nature when occuring in the superius and when occuring in the lower voices. It is common for the entirety of the superius to be written without any accidentals or for some of its notes to have an incorrect rhythmic value assigned ( | Regarding octave displacement, a lowercase letter belongs to the octave directly below Middle C, and an uppercase letter (only in 16th century sources) to the octave below that; for octaves above Middle C, horizontal lines should be progressively added above the lowercase letter. Note that, as the higher ranges were usually occupied by the superius, it is rare for the letters to intrude into the double-dashed octave - the specific implementation tends to vary between sources, with some lacking the provisions for such notation entirely. The rhythm is denoted with dots and vertical lines above the letters, as simplifications of the normal noteheads and stems used by mensural staff notation. Given that the shapes of the notes must agree between the superius and the letters below, a note with a dot above its letter has the note value of a semibrevis. Earlier sources tend to write "pausa" (or its shortened form, "pau") instead of a proper rest, and "vacat" if one or more voices are to stay silent for a whole measure. "Pausa" was also used to indicate that a previously struck note is to be sustained over the entirety of the next measure. | ||

Pedal parts (usually identifiable through a general absence of the shortest note values) tend to be given a prominent spot among letter-notated voices, that is, as the one that is placed highest or lowest. | |||

=== Other === | |||

Where measure lines were not written, the scribe denoted the limits of measures with minute horizontal gaps between groups of letters. A "=" symbol (oriented vertically if used at the bottom of a page) at a measure which was cut off prematurely by the right margin serves to let the reader know that a continuation will follow. Notes can be written across barlines. | |||

Scribal errors happen often, as do intentional omissions of commonly understood interpretative details, and they are of different nature when occuring in the superius and when occuring in the lower voices. It is common for the entirety of the superius to be written without any accidentals, or for some of its notes to have an incorrect rhythmic value assigned (by inappropriate usage of either stems or flags, or both). Somewhat less frequently, accidentals were left out in the lower voices as well. Sections of the top voice are also prone to being written a line too high or too low, producing unmusical results. Similarly to other polyphonic sources in common mensural notation, there are many cases where the total length of a measure in the superius does not match itself as given by the letters. | |||

Another detail in which the old tablature differs from the new one is the arrangement of music on a manuscript's pages: although a specific scribal error in the tablature of Jan of Lublin confirms the existence of sources in which the music was written across two opposing pages, all surviving manuscripts were written from the top down in single pages. | |||

== Specific manuscripts == | == Specific manuscripts == | ||

''More details and links will be added | ''The following paragraphs attempt to summarise the differences in the style of notation among families of surviving manuscripts, as well as between individual manuscripts of one group. More details and links will be added over time.'' | ||

=== Early sources and fragments === | |||

* [[A-Wnhd Cod. 3617]], a single setting of Kyrie V ("Magne Deus") inserted into a several-hundred-page theological manuscript. The meter is "octo notarum", and the syllables of the text (including the trope) are written next to the letter notation. | |||

* [[PL-WRu I Q 438|The Żagań fragment]], a loose folio with three Gloria versets. | |||

* [[PL-WRu I Q 42|The Wrocław manuscript]], with one tenor setting of a popular song and the beginning of a fundamentum appended to a compilation of theological texts. | |||

* [[D-Mbs Clm 5963]], where a Magnificat setting was inserted between various unrelated texts (on f. 248, marked as 240 in the original). Neumes can also be found elsewhere in the source. | |||

* [[D-Mbs Clm 7755]], a treatise about organ composition, including several short pedagogical pieces, ending with a song setting. Most of the manuscript is taken up by medical texts. | |||

The letter notation in this source is unique: to save space, two-voice accompaniment is written horizontally, so that a pair of letters always takes up the space below a single "measure" in the superius. It is commonly accepted that this signifies the usage of double pedal, the left letter being intended for the left foot and likewise on the right side. ''Further comment on this manuscript is precluded by lack of access to its facsimile or published research of acceptable quality''. | |||

* [[D-Kstb 4° Ms.theol. 18]], where a single page of untitled tablature precedes a psalter. | |||

* [[D-B Ms.theol.lat.qu. 290|The tablature of Ludolf Wilkin]]. ''Currently being digitised, according to the library's online catalogue.'' | |||

* [[D-OLI Cim I 39|The Oldenburg tablature]], attributed to Ludolf Bödeker, containing several free pieces, a short fundamentum, and a setting of the Credo. The rest of the manuscript contains neumes for plainchant settings of various parts of the Mass Ordinary and a few sequences. | |||

* [[D-Hs ND VI 3225|The tablature of Wolfgang von Neuhaus]]. Two sets of tablature can be found within, along with several pages of unrelated text, and both mostly consist of instructive pieces. | |||

* [[Ileborgh Tablature|Ileborgh tablature]]. The letter notation in this source is unique: to save space, two-voice accompaniment is written horizontally, so that a pair of letters always takes up the space below a single "measure" in the superius (although most pieces in this manuscript are unmeasured). It is commonly accepted that this signifies the usage of double pedal, the left letter being intended for the left foot and likewise on the right side. ''Further comment on this manuscript is precluded by lack of access to its facsimile or published research of acceptable quality''. | |||

In the music of these sources, as a rule, the tenor only has one note in a measure, and rhythm marks are therefore absent. Moreover, the specific subdivision of tenor notes is often provided at a piece's beginning (such as "trium", "quattuor", or "sex notarum"), a practice also observed among the earlier entries in the Buxheim manuscript. In accordance, measure lines are drawn regularly; only in the free, unmeasured praeambula are they absent. | |||

=== Sources before 1500 === | |||

In these sources, notes deeper than an octave below Middle C are notated with lowercase letters, as are those directly above them, and thus their reading may be uncertain. Said deep notes are most commonly encountered at the penultimate steps of cadences, where the "lower alternative" is necessary in order to avoid a second-inversion triad. A unified and unambiguous system of rhythmic notation for the lower voices can now be observed across several manuscripts. In the superius, each note has its flags written separately, even in cases where beaming was possible. | |||

==== [[PL-WRu I F 687]] ==== | |||

The lower voices are only provided rhythm signs in the last two pieces of this source; the preceding ones use no such notation, similarly to the manuscripts listed above. Some notes in the superius are flipped to avoid intruding too far above the staff; the staff has six lines, and another line is used to separate adjacent systems. Accidentals are notated in the common manner, the downward stem often not being crossed. The "double-stemmed note" (see section on Lochamer-Liederbuch below) appears several times with varying meanings: in at least three cases, it serves as a ''custos'' pointing out the pitch of the first note on the next staff. | |||

==== [[Lochamer-Liederbuch]] ==== | ==== [[Lochamer-Liederbuch]] ==== | ||

The second half of the manuscript (that is, the part which contains pieces in organ tablature) can be further divided into two sections according to the manner in which the notation was written. The point at which a new octave begins was chosen to be between ''B'' and ''H'', for practical reasons. Except for staves written later into the bottom margin in order to keep a piece within the boundaries of a single page, every staff has seven lines. For the clef, the letters ''C'', ''G'', and ''D'' are used, with abstract symbols for ''F'' and ''D'' (a flower). | The second half of the manuscript (that is, the part which contains pieces in organ tablature) can be further divided into two sections according to the manner in which the notation was written. The point at which a new octave begins was chosen to be between ''B'' and ''H'', for practical reasons. Except for staves written later into the bottom margin in order to keep a piece within the boundaries of a single page, every staff has seven lines. For the clef, the letters ''C'', ''G'', and ''D'' are used, with abstract symbols for ''F'' and ''D'' (a flower). | ||

* The first section is written in a clear and legible hand. It gives an overall impression of a standardised, consistent system of notation, with only minimal deviations from the norm. Barlines are present and most measures have a regular length of three semibreves (this suggests that ''tempus perfectum'' is assumed); only a few measures are longer than that, typically two or three times the normal amount. In the superius, chromatic inflections use a crossed downward stem. A looping downward stem, identical both in shape and usage to that present in the Buxheim manuscript, is used in the last two pieces ("''Benedicite Almechtiger got''" and "''Domit ein gut Jare''"). Outside of that, it appears that the only notation for an ornament is a double-stemmed notehead with flags on both stems. It typically occurs in passages of uniformly-moving minims, only twice (towards the end of the "''Fundamentum breve cum ascensu et descensu''") does it appear in contexts where the Buxheim loop may be considered appropriate. However, Apel claims that it is identical to a semiminim, specifically one on the weak beat, always adding a dot to the preceding minim when transcribing. | * The first section is written in a clear and legible hand. It gives an overall impression of a standardised, consistent system of notation, with only minimal deviations from the norm. Barlines are present and most measures have a regular length of three semibreves (this suggests that ''tempus perfectum'' is assumed); only a few measures are longer than that, typically two or three times the normal amount. In the superius, chromatic inflections use a crossed downward stem. A looping downward stem, identical both in shape and usage to that present in the Buxheim manuscript, is used in the last two pieces ("''Benedicite Almechtiger got''" and "''Domit ein gut Jare''"). Outside of that, it appears that the only notation for an ornament is a double-stemmed notehead with flags on both stems. It typically occurs in passages of uniformly-moving minims, only twice (towards the end of the "''Fundamentum breve cum ascensu et descensu''") does it appear in contexts where the Buxheim loop may be considered appropriate (the double-stemmed symbol does appear in the Buxheim manuscript as well, though extremely rarely). However, Apel claims that it is identical to a semiminim, specifically one on the weak beat, always adding a dot to the preceding minim when transcribing. | ||

: Out of the lower voices, the tenor is written in large black letters, with a double letter being used for its last note (invariably a ''longa''). Note that the symbol for a final ''D'' somewhat resembles that which later notation uses for a common ''Es'', and, similarly, a double ''G'' may | : Out of the lower voices, the tenor is written in large black letters, with a double letter being used for its last note (invariably a ''longa''). Note that the symbol for a final ''D'' somewhat resembles that which later notation uses for a common ''Es'', and, similarly, a double ''G'' may look similar to a ''Gis''. At the beginning of a piece or section thereof, a capital, sometimes double, letter is used. Very rarely, multiple letters occur in other places as well; the meaning of such usage is obscure. In some such cases, it may refer to repetition of a note, or perhaps to signify that an unusually long note is to be played. No notation is used for notes of the double-dashed octave, as the lower voices never move higher than g'. The contratenor may be written in either red or black ink, its letters appearing both above and below those of the tenor. Note values are written in red ink above the letters, but only in cases where there are more than three notes in one measure. | ||

* The latter part is distinct by the absence of decorative red ink (except for two pages) and prevalence of white mensural notation for the superius; it begins with black notation, but eventually moves to white midway through a piece (the "''Paumgartner''"), suggesting that the scribe first wrote empty noteheads and intended to fill them in later. A greatly expanded selection of keys is now available for the lower voices: the notes ''Es'', ''Fis'', ''Gis'', and even ''Dis'' (in an incorrect context, no less) appear in this section for the first time. While still clearly legible, the handwriting is not as orderly as before. In the second-to-last "''Praeambulum super F''", | * The latter part is distinct by the absence of decorative red ink (except for two pages) and prevalence of white mensural notation for the superius; it begins with black notation, but eventually moves to white midway through a piece (the "''Paumgartner''"), suggesting that the scribe first wrote empty noteheads and intended to fill them in later. A greatly expanded selection of keys is now available for the lower voices: the notes ''Es'', ''Fis'', ''Gis'', and even ''Dis'' (in an incorrect context, no less) appear in this section for the first time. While still clearly legible, the handwriting is not as orderly as before. In the second-to-last "''Praeambulum super F''", two voices are written in the first staff, forming a plain chordal texture with the third voice below. The tablature on the last page returns to the notational practice observed throughout the first section, albeit less decorated. | ||

==== [[Buxheim Organ Book|The Buxheim organ book]] ==== | ==== [[Buxheim Organ Book|The Buxheim organ book]] ==== | ||

Throughout the manuscript, seven lines are used for staves, exceptions being the six staves of five lines following the last piece of the collection, as well as the extensive "''Tabula''" on the last folio, which uses twelve lines and serves to explain the | Throughout the manuscript, seven lines are used for staves, exceptions being the six staves of five lines following the last piece of the collection, as well as the extensive "''Tabula''" on the last folio, which uses twelve lines and serves to explain the notation. The clef predominantly uses the standard "ut" symbol for the ''C'', with small vertical dashes for the ''G'' and ''D'' above; of these, the ''G'' ocassionally uses a letter, and may appear by itself. An F-clef only occurs in the aforementioned Tabula. Rests are now represented with proper symbols indicating their exact lengths. Usage of proportions in the superius can be easily identified, as it is represented a markedly different style of notation for the superius; large note values are written in void notation, a practice reminiscent of ''color'', while smaller ones receive the aforementioned triangular flag. In addition, a simple description of the change at hand (most often "''sexquialtera''") was added in some cases. Where a brevis needs to be chromatically altered, the downward stem almost always receives the diagonal dash, to prevent confusion with a longa. A fermata is sometimes used to denote the ends of musical sub-sections, similarly to its use in vocal compositions of the time. | ||

* Out of the nine fascicles that constitute the manuscript, almost all music in the first eight was written by a single scribe, with five pieces added at the end in another hand. The handwriting observed throughout this corpus is orderly and legible, with all notes of a measure evenly spaced across its width. Barlines are present; as in the Lochamer source, a measure may sometimes take on a whole-number multiple of the regular length. White mensural notation appears in two pieces here. A third scribe added a single untitled piece (No. 239) at the beginning of the ninth fascicle, showing no significant differences from the established style. | * Out of the nine fascicles that constitute the manuscript, almost all music in the first eight was written by a single scribe, with five pieces added at the end in another hand. The handwriting observed throughout this corpus is orderly and legible, with all notes of a measure evenly spaced across its width. Barlines are present; as in the Lochamer source, a measure may sometimes take on a whole-number multiple of the regular length. White mensural notation appears in two pieces here. A third scribe added a single untitled piece (No. 239) at the beginning of the ninth fascicle, showing no significant differences from the established style. A new octave begins between ''H'' and ''C'', with ocassional slips where the intabulator added an overscore over an ''H''. | ||

* The fourth successive scribe of the Buxheim organ book | * The fourth successive scribe of the Buxheim organ book was the first to make extensive use of the aforementioned superius shorthand, omitting stems in a group of notes of identical note values, except for the first (a few earlier occurences may be found, but they seem to be accidental). Aside from the crossed downward stem, the standard sharp symbol of mensural notation is used in several places. The point of division between octaves is inconsistent, but it appears the scribe intended for a higher octave to start at ''B''-''H''. For the most part, the scribe omitted barlines - they are only present where the boundary would be difficult to find from the notes alone, and double barlines are used to separate sections of a single fundamentum. | ||

* Two pieces, No. 238b and No. 239, were each entered by a single scribe. The former returns to the original system of beginning a new octave with ''C''. Despite having notably different handwriting from the previous four scribes, neither of the two makes use of any original notational devices, aside from a clef made of the three letters ''C'', ''G'', and ''D'', exactly as they would appear in tablature, with single | * Two pieces, No. 238b and No. 239, were each entered by a single scribe. The former returns to the original system of beginning a new octave with ''C''. Despite having notably different handwriting from the previous four scribes, neither of the two makes use of any original notational devices, aside from a clef made of the three letters ''C'', ''G'', and ''D'', exactly as they would appear in tablature, with a single overscore to indicate their high pitch. The first piece has measure lines, the second does not. From No. 239 onward, stems and flags are no longer omitted in the superius. | ||

* Scribe 7, having written pieces No. 240 through No. 244, used a letter for the ''D'' in the clef and only provided barlines once. | * Scribe 7, having written pieces No. 240 through No. 244, used a letter for the ''D'' in the clef and only provided barlines once. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 81: | ||

* The next, who contributed eight pieces, is notable for an unusual symbol somewhat similar in usage to the modern ''segno'': a circle from which a cross protrudes is used both to divert the performer when playing through a repetition, and to mark the beginning of the "''secunda volta''" in question. The only semblance of measure lines appears where there is a need to separate two pieces on the same staff, and the horizontal spacing between grouped notes varies from minimal to nonexistent. | * The next, who contributed eight pieces, is notable for an unusual symbol somewhat similar in usage to the modern ''segno'': a circle from which a cross protrudes is used both to divert the performer when playing through a repetition, and to mark the beginning of the "''secunda volta''" in question. The only semblance of measure lines appears where there is a need to separate two pieces on the same staff, and the horizontal spacing between grouped notes varies from minimal to nonexistent. | ||

* A ninth scribe wrote down five pieces, beginning with No. 252 ("''Tant apart''"). They added | * A ninth scribe wrote down five pieces, beginning with No. 252 ("''Tant apart''"). They added an overscore to the ''H'' below Middle C about as often as they omitted them, which is in sharp contrast to the generally consistent observation of the ''H''-''C'' divide shown by the other authors. | ||

* The tenth and last scribe, of considerably less legible handwriting than their predecessors, entered the two last pieces of the corpus. Their first intabulation has no barlines, the second uses them consistently, and, once again, seems to echo the style in which the first compositions of the manuscript were written down. | * The tenth and last scribe, of considerably less legible handwriting than their predecessors, entered the two last pieces of the corpus. Their first intabulation has no barlines, the second uses them consistently, and, once again, seems to echo the style in which the first compositions of the manuscript were written down. | ||

According to the Tabula, notes an octave above Middle C or higher should be notated identically to their lower counterparts - with only one overcore. Uppercase letters are used at the beginning of almost every piece or section thereof, as an initial. | |||

=== Sources after 1500 === | |||

These newer sources present some differences from earlier attempts at notating organ music. Most notably, the ambiguity of whether a note belongs to the great or small octave is eliminated (for which Schlick's solution differs from the common practice of using uppercase letters). Another "advancement" is the consistent use of proper mensuration symbols, where necessary, in the middle of a piece, which corresponds to the decreased use of ''color'' in only one voice at a time. Furthermore, a constant 2:1 ratio of diminution was adopted for intabulations, so that what was written as a semibrevis would represent a brevis in vocal notation (in the present article, this will not be taken into account, and note values will be named according to their visual value). The omission of stems and flags in the superius becomes standard, at times spreading to the lower voices as well, and small groups of notes may appear with various kinds of beaming - more often in the superius than in letters - depending on the scribe's manner of handwriting. The gamut is typically divided into octaves between ''B'' and ''H''. | |||

==== [[Tabulaturen Etlicher Lobgesang|Tabulaturen etlicher Lobgesang und Lidlein]] ==== | ==== [[Tabulaturen Etlicher Lobgesang|Tabulaturen etlicher Lobgesang und Lidlein]] ==== | ||

As the only surviving example of printed old tablature - and possibly the earliest instance of printed organ music - the notation of [[Arnolt Schlick|Schlick's]] ''Tabulaturen'' differs | As the only surviving example of printed old tablature - and possibly the earliest instance of printed organ music - the notation of [[Arnolt Schlick|Schlick's]] ''Tabulaturen'' differs from that of the other sources. The staff has six lines, and every note is printed complete with its stem and flags. Some of the notes that are placed on or below the top line are flipped in such a way that their stem points down. Chromatic alteration is indicated by a small loop connected to the notehead, opposite the stem. There are no symbols for ornaments of any kind. Sections in perfect time use looped, almost triangular flags on their semiminims and fusae. Like in the Buxheim organ book, lowercase letters are used for notes of the great octave; however, Schlick eliminates ambiguity by adding a horizontal line below the letter. A new octave begins with ''C''. For notes more than an octave above Middle C, only a single overscore is used, but the letter is doubled. | ||

==== [[Fundamentum of Hans Buchner]] ==== | ==== [[CH-Bu F I 8a|Fundamentum of Hans Buchner]] ==== | ||

Outside of using "modern" beaming for groups of notes shorter than semiminims, the notation doesn't depart from the conventions described above. High notes use double overscores instead of doubled letters. ''The other Buchner manuscript in the possession of Zentralbibliothek Zürich was not available for perusal, but is likely to use the same conventions, as both were written by the same scribe.'' | |||

==== [[Hans Kotter | ==== [[CH-Bu F IX 22]] ("large" tablature of Hans Kotter) ==== | ||

Notes above C5 are represented with double letters and a single overscore, as in Schlick's published works. A staff of six lines is used throughout. | |||

==== [[ | ==== [[CH-Bu F IX 58]] ("small" tablature of Hans Kotter)==== | ||

This manuscript also uses a six-line staff. High notes do appear (in the "Kochersperger Spanioler"), but are not represented differently from those below them. | |||

==== [[ | ==== [[CH-Bu F VI 26c|Holtzach fragment]] ==== | ||

A five-line staff is used for the theoretical examples at the beginning of the tablature, while the following organ compositions and intabulations use a staff of six lines. No notes above C5 occur in the tablature proper; there is, however, an explicatory depiction of the keyboard in the first section of the manuscript, where they are notated using double letters with an overscore. | |||

==== [[Tablature | ==== [[CH-SGs Cod. Sang. 530|Fridolin Sicher tablature]] ==== | ||

To notate binary note values in sections that use (a proportion effectively equivalent to) ternary divisions, the noteheads in question are supplied with two stems, each having a looped flag of its own. The staff alternates between five and six lines. | |||

==== [[D-B Mus.ms. 40026|Leonhard Kleber tablature]] ==== | |||

Kleber seemingly used a five-line staff as his default, readily adding more lines to it when such an extension was needed. | |||

==== [[CH-Bu F IX 57]] ==== | |||

The handwriting of this source's author is, in comparison with other manuscripts written often quite diligently, remarkably even and regular. The source often uses uncharacteristically generous beaming in the lower voices, but in other places also applies to them the omission of stems commonly used for the superius. A staff of five lines is used throughout, and no observation about the notation of high notes in letters can be made, as they do not occur in either of the two compositions. | |||

=== Other sources === | |||

''Facsimiles of these manuscripts were not available at the time of writing.'' | |||

==== [[CH-Zz Z. XI. 301|Clemens Hör tablature]] ==== | |||

==== [[Jan of Lublin Tablature|Jan of Lublin tablature]] ==== | |||

==== [[Cracow Tablature|Cracow tablature]] ==== | ==== [[Cracow Tablature|Cracow tablature]] ==== | ||

| Line 67: | Line 126: | ||

''Facsimiles of the aforementioned manuscripts can be accessed from their respective pages''. | ''Facsimiles of the aforementioned manuscripts can be accessed from their respective pages''. | ||

Kite-Powell, J. (2022) ''German Keyboard Tablature''. https://www.academia.edu/53290890/German_Keyboard_Tablature | Kite-Powell, J. (2022). ''German Keyboard Tablature''. https://www.academia.edu/53290890/German_Keyboard_Tablature | ||

Aringer, K (2006). ''Ein Unbekanntes Orgeltabulatur-Fragment des 15. Jahrhunderts in der Erzabtei St. Peter (Salzburg)''. Die Musikforschung, vol. 59. | |||

Meyer, Ch. (2000). ''A Propos d’Un Feuillet de Tablature d’Orgue du Milieu du XVe S.''. https://hal.science/hal-00438192 | |||

Marx, W (1998). ''Die Orgeltabulatur des Wolfgang de Nova Domo''. Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, vol. 55. | |||

Warburton, T. A. (1969). ''Fridolin Sicher's Tablature: A Guide to Keyboard Performance of Vocal Music''. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan. | |||

Apel, W. (1967). ''Geschichte der Orgel- und Klaviermusik bis 1700''. Kassel, Bärenreiter-Verlag. | |||

Southern, E. (1963). ''The Buxheim Organ Book''. Brooklyn, Institute of Mediaeval Music. | |||

White, J. R. (1963). ''The Tablature of Johannes of Lublin''. Musica Disciplina, vol. 17. | |||

Young, W. (1962). ''Keyboard Music to 1600 I''. Musica Disciplina, vol. 16. | |||

Lord, R. S. (1960). ''The Buxheim Organ Book: A Study in the History of Organ Music in Southern Germany During the Fifteenth Century''. Doctoral dissertation, Yale University. | |||

Apel, W. (1938). ''Early German keyboard music''. The Musical Quarterly, vol. 23. | |||

Merian, W. (1916). ''Die Tabulaturen des Organisten Hans Kotter''. Doctoral dissertation, Basel University. | |||

Loewenfeld, H. (1897). ''Leonhard Kleber und sein Orgeltabulaturbuch als Beitrag zur Geschichte der Orgelmusik im beginnenden XVI. Jahrhundert''. Doctoral dissertation, Humboldt University, Berlin. | |||

Latest revision as of 17:42, 12 November 2024

The term "Old German Tablature" refers to a style of notation popular among German-speaking organists in the 15th and 16th century. Unlike the "new" notation, it was only rarely used to write down compositions not to be played on a keyboard instrument. Surviving examples show that it could readily support pieces between two and six voices. Examples of more developed notational styles seem to have originated in southern and south-western Germany in two main groups centered around particularly respected organists (Conrad Paumann and Paul Hofhaimer respectively).

General overview

The defining feature of old German tablature is the usage of black mensural notation for the voice that is highest in pitch (the superius, as it is often referred to). The organist is usually expected to play this voice in their right hand, using their other hand and both feet to play the lower voices, which are invariably given in letters. The specific style of notation varies significantly between manuscripts, but a few common elements can be observed:

Superius

In the superius, all stems point upwards, and a downward stem is used to denote chromatic inflections (if it appears plain or crossed with a short, diagonal stroke) or ornamentation (with a loop or curve at its end). Some scribes allow for downward stems that are both crossed and looped, some prefer to only denote the ornament in such cases. A triangular flag may denote proportions or a change in mensuration, typically to signify temporary ternary division of note values when binary division is used throughout the rest of the piece (the Buxheim manuscript, which uses generally larger note values than later sources, utilises the standard technique of color in cases where such a change occurs among note values too large to be written with flags). In the last third of the 15th century, a curious form of shorthand emerged - in a passage of many notes moving in uniform values, only the first is given with the appropriate amount of flags, while the rest are notated as noteheads only. A double-sided repetition symbol, the shape of which varies between sources but always remains recognisable, can be placed above the staff, wherever it is most appropriate - the specific manner in which the repetition is to be carried out depends on the musical context. The custos appears often, though not everywhere.

Lower voices

Note: Even though the letter notation may look similar to its counterpart in the "New" tablature notation, there are some differences between the two.

In the lower voices, the symbols used generally agree with what is now known as Helmholtz pitch notation: the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, H belong to the white keys, while for the black keys a specific set of Cis, Es (or Dis), Fis, Gis, B is used. These are used even in contexts where the enharmonic spelling should be preferable, with minimal exceptions (presumably for the sake of convenience). At first, the symbols of the black keys may prove difficult to recognise: the raised tones are only written with the base letter and a long S next to it, the I being omitted, and Es, despite being written without any shorthand, tends to become distorted by the scribes' handwriting - in later sources (and most manuscripts written in the newer style), the symbol is formed differently and represents a Dis note instead.

Regarding octave displacement, a lowercase letter belongs to the octave directly below Middle C, and an uppercase letter (only in 16th century sources) to the octave below that; for octaves above Middle C, horizontal lines should be progressively added above the lowercase letter. Note that, as the higher ranges were usually occupied by the superius, it is rare for the letters to intrude into the double-dashed octave - the specific implementation tends to vary between sources, with some lacking the provisions for such notation entirely. The rhythm is denoted with dots and vertical lines above the letters, as simplifications of the normal noteheads and stems used by mensural staff notation. Given that the shapes of the notes must agree between the superius and the letters below, a note with a dot above its letter has the note value of a semibrevis. Earlier sources tend to write "pausa" (or its shortened form, "pau") instead of a proper rest, and "vacat" if one or more voices are to stay silent for a whole measure. "Pausa" was also used to indicate that a previously struck note is to be sustained over the entirety of the next measure.

Pedal parts (usually identifiable through a general absence of the shortest note values) tend to be given a prominent spot among letter-notated voices, that is, as the one that is placed highest or lowest.

Other

Where measure lines were not written, the scribe denoted the limits of measures with minute horizontal gaps between groups of letters. A "=" symbol (oriented vertically if used at the bottom of a page) at a measure which was cut off prematurely by the right margin serves to let the reader know that a continuation will follow. Notes can be written across barlines.

Scribal errors happen often, as do intentional omissions of commonly understood interpretative details, and they are of different nature when occuring in the superius and when occuring in the lower voices. It is common for the entirety of the superius to be written without any accidentals, or for some of its notes to have an incorrect rhythmic value assigned (by inappropriate usage of either stems or flags, or both). Somewhat less frequently, accidentals were left out in the lower voices as well. Sections of the top voice are also prone to being written a line too high or too low, producing unmusical results. Similarly to other polyphonic sources in common mensural notation, there are many cases where the total length of a measure in the superius does not match itself as given by the letters.

Another detail in which the old tablature differs from the new one is the arrangement of music on a manuscript's pages: although a specific scribal error in the tablature of Jan of Lublin confirms the existence of sources in which the music was written across two opposing pages, all surviving manuscripts were written from the top down in single pages.

Specific manuscripts

The following paragraphs attempt to summarise the differences in the style of notation among families of surviving manuscripts, as well as between individual manuscripts of one group. More details and links will be added over time.

Early sources and fragments

- A-Wnhd Cod. 3617, a single setting of Kyrie V ("Magne Deus") inserted into a several-hundred-page theological manuscript. The meter is "octo notarum", and the syllables of the text (including the trope) are written next to the letter notation.

- The Żagań fragment, a loose folio with three Gloria versets.

- The Wrocław manuscript, with one tenor setting of a popular song and the beginning of a fundamentum appended to a compilation of theological texts.

- D-Mbs Clm 5963, where a Magnificat setting was inserted between various unrelated texts (on f. 248, marked as 240 in the original). Neumes can also be found elsewhere in the source.

- D-Mbs Clm 7755, a treatise about organ composition, including several short pedagogical pieces, ending with a song setting. Most of the manuscript is taken up by medical texts.

- D-Kstb 4° Ms.theol. 18, where a single page of untitled tablature precedes a psalter.

- The tablature of Ludolf Wilkin. Currently being digitised, according to the library's online catalogue.

- The Oldenburg tablature, attributed to Ludolf Bödeker, containing several free pieces, a short fundamentum, and a setting of the Credo. The rest of the manuscript contains neumes for plainchant settings of various parts of the Mass Ordinary and a few sequences.

- The tablature of Wolfgang von Neuhaus. Two sets of tablature can be found within, along with several pages of unrelated text, and both mostly consist of instructive pieces.

- Ileborgh tablature. The letter notation in this source is unique: to save space, two-voice accompaniment is written horizontally, so that a pair of letters always takes up the space below a single "measure" in the superius (although most pieces in this manuscript are unmeasured). It is commonly accepted that this signifies the usage of double pedal, the left letter being intended for the left foot and likewise on the right side. Further comment on this manuscript is precluded by lack of access to its facsimile or published research of acceptable quality.

In the music of these sources, as a rule, the tenor only has one note in a measure, and rhythm marks are therefore absent. Moreover, the specific subdivision of tenor notes is often provided at a piece's beginning (such as "trium", "quattuor", or "sex notarum"), a practice also observed among the earlier entries in the Buxheim manuscript. In accordance, measure lines are drawn regularly; only in the free, unmeasured praeambula are they absent.

Sources before 1500

In these sources, notes deeper than an octave below Middle C are notated with lowercase letters, as are those directly above them, and thus their reading may be uncertain. Said deep notes are most commonly encountered at the penultimate steps of cadences, where the "lower alternative" is necessary in order to avoid a second-inversion triad. A unified and unambiguous system of rhythmic notation for the lower voices can now be observed across several manuscripts. In the superius, each note has its flags written separately, even in cases where beaming was possible.

PL-WRu I F 687

The lower voices are only provided rhythm signs in the last two pieces of this source; the preceding ones use no such notation, similarly to the manuscripts listed above. Some notes in the superius are flipped to avoid intruding too far above the staff; the staff has six lines, and another line is used to separate adjacent systems. Accidentals are notated in the common manner, the downward stem often not being crossed. The "double-stemmed note" (see section on Lochamer-Liederbuch below) appears several times with varying meanings: in at least three cases, it serves as a custos pointing out the pitch of the first note on the next staff.

Lochamer-Liederbuch

The second half of the manuscript (that is, the part which contains pieces in organ tablature) can be further divided into two sections according to the manner in which the notation was written. The point at which a new octave begins was chosen to be between B and H, for practical reasons. Except for staves written later into the bottom margin in order to keep a piece within the boundaries of a single page, every staff has seven lines. For the clef, the letters C, G, and D are used, with abstract symbols for F and D (a flower).

- The first section is written in a clear and legible hand. It gives an overall impression of a standardised, consistent system of notation, with only minimal deviations from the norm. Barlines are present and most measures have a regular length of three semibreves (this suggests that tempus perfectum is assumed); only a few measures are longer than that, typically two or three times the normal amount. In the superius, chromatic inflections use a crossed downward stem. A looping downward stem, identical both in shape and usage to that present in the Buxheim manuscript, is used in the last two pieces ("Benedicite Almechtiger got" and "Domit ein gut Jare"). Outside of that, it appears that the only notation for an ornament is a double-stemmed notehead with flags on both stems. It typically occurs in passages of uniformly-moving minims, only twice (towards the end of the "Fundamentum breve cum ascensu et descensu") does it appear in contexts where the Buxheim loop may be considered appropriate (the double-stemmed symbol does appear in the Buxheim manuscript as well, though extremely rarely). However, Apel claims that it is identical to a semiminim, specifically one on the weak beat, always adding a dot to the preceding minim when transcribing.

- Out of the lower voices, the tenor is written in large black letters, with a double letter being used for its last note (invariably a longa). Note that the symbol for a final D somewhat resembles that which later notation uses for a common Es, and, similarly, a double G may look similar to a Gis. At the beginning of a piece or section thereof, a capital, sometimes double, letter is used. Very rarely, multiple letters occur in other places as well; the meaning of such usage is obscure. In some such cases, it may refer to repetition of a note, or perhaps to signify that an unusually long note is to be played. No notation is used for notes of the double-dashed octave, as the lower voices never move higher than g'. The contratenor may be written in either red or black ink, its letters appearing both above and below those of the tenor. Note values are written in red ink above the letters, but only in cases where there are more than three notes in one measure.

- The latter part is distinct by the absence of decorative red ink (except for two pages) and prevalence of white mensural notation for the superius; it begins with black notation, but eventually moves to white midway through a piece (the "Paumgartner"), suggesting that the scribe first wrote empty noteheads and intended to fill them in later. A greatly expanded selection of keys is now available for the lower voices: the notes Es, Fis, Gis, and even Dis (in an incorrect context, no less) appear in this section for the first time. While still clearly legible, the handwriting is not as orderly as before. In the second-to-last "Praeambulum super F", two voices are written in the first staff, forming a plain chordal texture with the third voice below. The tablature on the last page returns to the notational practice observed throughout the first section, albeit less decorated.

The Buxheim organ book

Throughout the manuscript, seven lines are used for staves, exceptions being the six staves of five lines following the last piece of the collection, as well as the extensive "Tabula" on the last folio, which uses twelve lines and serves to explain the notation. The clef predominantly uses the standard "ut" symbol for the C, with small vertical dashes for the G and D above; of these, the G ocassionally uses a letter, and may appear by itself. An F-clef only occurs in the aforementioned Tabula. Rests are now represented with proper symbols indicating their exact lengths. Usage of proportions in the superius can be easily identified, as it is represented a markedly different style of notation for the superius; large note values are written in void notation, a practice reminiscent of color, while smaller ones receive the aforementioned triangular flag. In addition, a simple description of the change at hand (most often "sexquialtera") was added in some cases. Where a brevis needs to be chromatically altered, the downward stem almost always receives the diagonal dash, to prevent confusion with a longa. A fermata is sometimes used to denote the ends of musical sub-sections, similarly to its use in vocal compositions of the time.

- Out of the nine fascicles that constitute the manuscript, almost all music in the first eight was written by a single scribe, with five pieces added at the end in another hand. The handwriting observed throughout this corpus is orderly and legible, with all notes of a measure evenly spaced across its width. Barlines are present; as in the Lochamer source, a measure may sometimes take on a whole-number multiple of the regular length. White mensural notation appears in two pieces here. A third scribe added a single untitled piece (No. 239) at the beginning of the ninth fascicle, showing no significant differences from the established style. A new octave begins between H and C, with ocassional slips where the intabulator added an overscore over an H.

- The fourth successive scribe of the Buxheim organ book was the first to make extensive use of the aforementioned superius shorthand, omitting stems in a group of notes of identical note values, except for the first (a few earlier occurences may be found, but they seem to be accidental). Aside from the crossed downward stem, the standard sharp symbol of mensural notation is used in several places. The point of division between octaves is inconsistent, but it appears the scribe intended for a higher octave to start at B-H. For the most part, the scribe omitted barlines - they are only present where the boundary would be difficult to find from the notes alone, and double barlines are used to separate sections of a single fundamentum.

- Two pieces, No. 238b and No. 239, were each entered by a single scribe. The former returns to the original system of beginning a new octave with C. Despite having notably different handwriting from the previous four scribes, neither of the two makes use of any original notational devices, aside from a clef made of the three letters C, G, and D, exactly as they would appear in tablature, with a single overscore to indicate their high pitch. The first piece has measure lines, the second does not. From No. 239 onward, stems and flags are no longer omitted in the superius.

- Scribe 7, having written pieces No. 240 through No. 244, used a letter for the D in the clef and only provided barlines once.

- The next, who contributed eight pieces, is notable for an unusual symbol somewhat similar in usage to the modern segno: a circle from which a cross protrudes is used both to divert the performer when playing through a repetition, and to mark the beginning of the "secunda volta" in question. The only semblance of measure lines appears where there is a need to separate two pieces on the same staff, and the horizontal spacing between grouped notes varies from minimal to nonexistent.

- A ninth scribe wrote down five pieces, beginning with No. 252 ("Tant apart"). They added an overscore to the H below Middle C about as often as they omitted them, which is in sharp contrast to the generally consistent observation of the H-C divide shown by the other authors.

- The tenth and last scribe, of considerably less legible handwriting than their predecessors, entered the two last pieces of the corpus. Their first intabulation has no barlines, the second uses them consistently, and, once again, seems to echo the style in which the first compositions of the manuscript were written down.

According to the Tabula, notes an octave above Middle C or higher should be notated identically to their lower counterparts - with only one overcore. Uppercase letters are used at the beginning of almost every piece or section thereof, as an initial.

Sources after 1500

These newer sources present some differences from earlier attempts at notating organ music. Most notably, the ambiguity of whether a note belongs to the great or small octave is eliminated (for which Schlick's solution differs from the common practice of using uppercase letters). Another "advancement" is the consistent use of proper mensuration symbols, where necessary, in the middle of a piece, which corresponds to the decreased use of color in only one voice at a time. Furthermore, a constant 2:1 ratio of diminution was adopted for intabulations, so that what was written as a semibrevis would represent a brevis in vocal notation (in the present article, this will not be taken into account, and note values will be named according to their visual value). The omission of stems and flags in the superius becomes standard, at times spreading to the lower voices as well, and small groups of notes may appear with various kinds of beaming - more often in the superius than in letters - depending on the scribe's manner of handwriting. The gamut is typically divided into octaves between B and H.

Tabulaturen etlicher Lobgesang und Lidlein

As the only surviving example of printed old tablature - and possibly the earliest instance of printed organ music - the notation of Schlick's Tabulaturen differs from that of the other sources. The staff has six lines, and every note is printed complete with its stem and flags. Some of the notes that are placed on or below the top line are flipped in such a way that their stem points down. Chromatic alteration is indicated by a small loop connected to the notehead, opposite the stem. There are no symbols for ornaments of any kind. Sections in perfect time use looped, almost triangular flags on their semiminims and fusae. Like in the Buxheim organ book, lowercase letters are used for notes of the great octave; however, Schlick eliminates ambiguity by adding a horizontal line below the letter. A new octave begins with C. For notes more than an octave above Middle C, only a single overscore is used, but the letter is doubled.

Fundamentum of Hans Buchner

Outside of using "modern" beaming for groups of notes shorter than semiminims, the notation doesn't depart from the conventions described above. High notes use double overscores instead of doubled letters. The other Buchner manuscript in the possession of Zentralbibliothek Zürich was not available for perusal, but is likely to use the same conventions, as both were written by the same scribe.

CH-Bu F IX 22 ("large" tablature of Hans Kotter)

Notes above C5 are represented with double letters and a single overscore, as in Schlick's published works. A staff of six lines is used throughout.

CH-Bu F IX 58 ("small" tablature of Hans Kotter)

This manuscript also uses a six-line staff. High notes do appear (in the "Kochersperger Spanioler"), but are not represented differently from those below them.

Holtzach fragment

A five-line staff is used for the theoretical examples at the beginning of the tablature, while the following organ compositions and intabulations use a staff of six lines. No notes above C5 occur in the tablature proper; there is, however, an explicatory depiction of the keyboard in the first section of the manuscript, where they are notated using double letters with an overscore.

Fridolin Sicher tablature

To notate binary note values in sections that use (a proportion effectively equivalent to) ternary divisions, the noteheads in question are supplied with two stems, each having a looped flag of its own. The staff alternates between five and six lines.

Leonhard Kleber tablature

Kleber seemingly used a five-line staff as his default, readily adding more lines to it when such an extension was needed.

CH-Bu F IX 57

The handwriting of this source's author is, in comparison with other manuscripts written often quite diligently, remarkably even and regular. The source often uses uncharacteristically generous beaming in the lower voices, but in other places also applies to them the omission of stems commonly used for the superius. A staff of five lines is used throughout, and no observation about the notation of high notes in letters can be made, as they do not occur in either of the two compositions.

Other sources

Facsimiles of these manuscripts were not available at the time of writing.

Clemens Hör tablature

Jan of Lublin tablature

Cracow tablature

References

Facsimiles of the aforementioned manuscripts can be accessed from their respective pages.

Kite-Powell, J. (2022). German Keyboard Tablature. https://www.academia.edu/53290890/German_Keyboard_Tablature

Aringer, K (2006). Ein Unbekanntes Orgeltabulatur-Fragment des 15. Jahrhunderts in der Erzabtei St. Peter (Salzburg). Die Musikforschung, vol. 59.

Meyer, Ch. (2000). A Propos d’Un Feuillet de Tablature d’Orgue du Milieu du XVe S.. https://hal.science/hal-00438192

Marx, W (1998). Die Orgeltabulatur des Wolfgang de Nova Domo. Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, vol. 55.

Warburton, T. A. (1969). Fridolin Sicher's Tablature: A Guide to Keyboard Performance of Vocal Music. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan.

Apel, W. (1967). Geschichte der Orgel- und Klaviermusik bis 1700. Kassel, Bärenreiter-Verlag.

Southern, E. (1963). The Buxheim Organ Book. Brooklyn, Institute of Mediaeval Music.

White, J. R. (1963). The Tablature of Johannes of Lublin. Musica Disciplina, vol. 17.

Young, W. (1962). Keyboard Music to 1600 I. Musica Disciplina, vol. 16.

Lord, R. S. (1960). The Buxheim Organ Book: A Study in the History of Organ Music in Southern Germany During the Fifteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Yale University.

Apel, W. (1938). Early German keyboard music. The Musical Quarterly, vol. 23.

Merian, W. (1916). Die Tabulaturen des Organisten Hans Kotter. Doctoral dissertation, Basel University.

Loewenfeld, H. (1897). Leonhard Kleber und sein Orgeltabulaturbuch als Beitrag zur Geschichte der Orgelmusik im beginnenden XVI. Jahrhundert. Doctoral dissertation, Humboldt University, Berlin.